Historical Background

Somaliland History#

Archeological Evidence#

Archeologists have discovered through meticulous and painstaking attention to detail that many of the ill-attended, yet-toexploited landscapes of Somaliland were, in fact, part of a region inhabited by the earliest modern humans, hundreds of thousands of years ago inhabited by the earliest-known pastoralists of northeast Africa as the spectacular rock art of this region indicates dating back to 5000 to 12 000 years.17

The paintings, the ancient towns ruin, and other traces marking the existence of past civilizations in the area still hold volumes of secrets that need to be unveiled.

Dr Sada Mire in a 2015 paper on Mapping the Archeology of Somaliland gives us a more detailed account of how important this part of the world has been to the world for eons past, stating that ‘the importance of this region is largely due to its location at the heart of ancient long-distance trade networks, making it a cultural crossroads.’

The coastal populations were active seafarers, facilitating not only transmission of goods (gold, ivory, slaves, aromatic oils, animal skins, and textiles from Africa, in return for silk, glass objects, spices and Chinese porcelains, etc.) but also ideas and cultures (The Archaeology of the Islamic Empires of the Horn of Africa: Ruined Towns (ca. Sixth–Seventeenth Century CE)). Maritime archaeology is on its way but terrestrial coastal material shows that the people of this region were part of the Silk Road trade. The archaeological evidence from the Somali region shows material from Tang Dynasty to Ming Dynasty China. All these networks, trade and institutions culminated in the Islamic Medieval empires of the Horn of Africa, such as the Ifat and Awdal(Adal) states (The Archaeology of the Islamic Empires of the Horn of Africa: Ruined Towns (ca. Sixth–Seventeenth Century CE)). The above claims are all indicated by the body of past and recent archaeological discoveries in Somaliland (and Somalia) that account for more than 200 sites, many of them clusters of sites. Hopefully, proper study of these sites will substantiate and show the significance of this region for world prehistory and history. 18Reference

A T Curle 19 states that “periodical reference to the ‘mysterious ruined cities of Somaliland’ citing them as an ‘unsolved riddle of Africa’ have appeared in books and articles from time to time.”Mr. Curle and Captain R. H. R. Taylor carried out a series of archeological investigations west of Hargeisa

Somaliland Before 1884#

The immediate region in which the Republic of Somaliland lies has been described as the ‘heart of ancient long-distance trade networks, making it a cultural crossroads’. 20 According to linguists, the first Afro-asiaticspeaking populations arrived during the ensuing Neolithic period from the family’s proposed urheimat (“original homeland”) in the Nile Valley, or the Near East.

Written circa 50 to 68 B.C. by a Greek writer or writers, the Periplus of the Eryhthraean in hthraean Sea, details a voyage that starts details a voyage that passes through some parts of present-day Somaliland on its way to the Indian subcontinent. Notably, among the flourishing, coastal trading posts the writers stopped to take note of were Avalites (Zeila), Malao (Berbera) and Mundus (Heiss). The description is unmistakable but, as is in the case of Heiss (a.k.a.Xiis or Hiis), location of proper town may have shifted several hundred yards to the east. Traces of the ancient town still show atop the promontory opposite the Ma’ajaleenka islet.

Somaliland” The True Land of Punt#

The fabled land of Punt that Egyptians so revered could by all calculations be the present-day Republic of Somaliland. Looking at the map of trade routes from Egypt to Punt via rivers, wadis, and by sea and the charted route of Queen Hatshepsut’s route during an expedition to the Land of Punt on the Red Sea coast in 1493 BCE in the 18th Dynasty of Egypt, there is no doubt the case is so.

Geographically, Somaliland is nearer to Egypt than Somalia, and as the items which the expedition found in the land of Punt is also abundantly available in Somaliland (gold, frankincense, myrrh, feathers, wildlife, etc.), logic dictates that the expedition needed not to travel any further for the same items and bypass Somaliland.

The Land of Punt was long associated with the goods in ancient Egyptian markets because materials from Punt were also used in their temple rituals. Priests wore leopard skins, gold became statuary, and incense was burned in the temples. Hatshepsut’s inscriptions also claim that her divine mother was from Punt - and there is evidence that Bes (the goddess of childbirth) came from Punt Land as well.

Punt Land became a semi-mythical land for the pharaohs, but it was a real place through the New Kingdom (1570-1069 BC). During the reign of Amunhotep II (1425-1400 BC) delegations from Punt were accepted. The reign of Ramesses II (1279-1213 BC) and of Ramesses III (1186-1155 BC) mentioned Punt as well. The pharaohs were fascinated by Punt as a “land of plenty” and it was best known as Ta Netjer – “God’s Land.

Political History#

The British Protectorate#

Somaliland, due to its strategic location near Bab el Mandeb, at the entrance to Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea, has always been of interest for strategic and commercial reasons. In the mid-16th century, the great Ottoman Empire annexed the port of Zeila and provided protection, at a cost collected through customs and other charges, for Arab, Persian and Indian merchants who serviced the trade requirements of the surrounding area and the Abyssinian hinterland.

In 1870 the ambitious Khedive Ismael I of Egypt, whose country was nominally part of the Ottoman Empire, obtained the Ottoman Sultan’s authorized rights over Zeila in exchange for paying an annual fee of sterling pounds 18,000. 23 The Khedive in due time acquired the coast between Bulhar and Berbera without reference to the Sultan.

In 1877 Britain signed a convention recognizing the Khedival annexation of all the East African coast north of Ras Hafun (the promontory of land jutting out into the Indian Ocean south of Cape Gardafui). The agreement stipulated that no portion of this area should be ceded to any foreign power and that British consular agents should be appointed at places on the coast. The Sultan of Turkey, hitherto not very interested in any land east of Zeila, generating, however, a piqued interest of the Ottoman Empire.

As Egypt had opened the Suez Canal in 1869, Egyptian interest shifted more on the coastline rather than the interior. At coastal locations lighthouses, harbors, piers, blockhouses, and barracks were constructed, and running water supplies engineered. Some of these facilities have lasted until recently.

In 1884 Egypt was facing the Mahdist revolt in the Sudan and for financial reasons (dictated by Britain) had to curtail its projects along the Somaliland coast. By agreement with Britain the Egyptian flag remained flying in Somaliland but Egyptian troops and officials were withdrawn and replaced by very few British troops, ships and officials from Aden.

Britain Sets Protectorate#

Shortly after Britain set garrisons in Aden, only 150 miles across the Berbera port of the Republic of Somaliland, in 1839, Somaliland became a source of fresh meat. With the departure of the Egyptians and the

possibility that other colonial powers had their eyes trained on the potentials of the Somaliland coasts and its hinterland, Britain had to act fast. The British colonial office expedited Major A. Hunt of Great, representing his government, to draw up protection treaties with several Somaliland clans.

Britain wooed Somaliland clan leaders with a promise of protection, guaranteeing them full support in case of an attack from other neighboring territories, which were then occupied by other Europeans (See The Map of Africa by Treaty written by Sir E. Hertslet). On their part, the clan elders of the day refused to grant the British the right to land unless they agreed to their terms.

The British agreed to the Somaliland conditions among which were: (a) that Somaliland was to be a Protectorate and not a colonial conquest, and (b) that no British baby was to be delivered on the mainland. Only after the agreement was finalized and signed on hide skin aboard a ship, was the British able to land. Soon after, Great Britain sent its Vice Consuls to the Somaliland coastal towns such as Berbera, Bulahar, and Zeila. Due to the relative stability brought on by the treaties, trading at coastal towns also briskly picked up.

Somaliland became British Protectorate/Colony in East Africa which not only balanced its books but had also constantly reported surpluses. The key to Somaliland’s opulence by African economic standards of the day was international trade, as the people in the territory were in the words of one British colonial officer, “Natural born traders.” (See “Somaliland” by Andrew Hamilton)

Sayyed Mohammed Abdulla Hassan was an articulate, tall, thin, dark-skinned man with a small beard and dark eyes who had an uncanny knack with word play and poetry.

A Mural of Sayyed Mohammed Abdulle Hassan painted to his likeness

Sayyed Mohammed is reported to have been born in 1856, which, in Somali lore, was called Gobaysane – a rich, prosperous year. The Sayyed studied under local religious scholars and perfected the holy book Quran, Sunna and other religious studies in no time. He undertook the Hajj and studied under Mohammed Salih in Mecca in the early 1890s – a name his sect so devoutly clung to until the end - Salihia.

Sayyed Mohammed Abdullah Hassan was to his adherents a messianic Sunni, freedom fighter. At the time he started the Dervish movement, he was seen as a liberator, a man not interested in this world, and a freedom fighter whose only objective was to drive the ‘colonials’ out from the world of Somalis – the British Protectorate. To a vast majority of Somalis and foreigners, especially, the British, Italians and the Ethiopians, he was the “Mad Mullah,” a quasi-religious bandit leader intent on plunder and disruption who imposed his will through savage executions and mutilations.

The Sayyed waged an active campaign against the British and clans that he labeled as loyalists to the Crown started as early 1899. It was reported that during this year he had amassed some 5000 men, 1500 of whom were mounted, under his command.

“I have no forts, no houses, no country. I have no cultivated fields, no silver or gold for you to take — all you can get from me is war, nothing else. I have met your men in battle and have killed them. We are greatly pleased about this. Our men who have fallen in battle have won paradise…”,

he stated in a letter he dispatched to the British Governor on the same year.

The British used superior firepower and masses of troops against the Sayyed and, at each confrontation, the British would proclaim victory. The fact remained, though, that the Sayyed always evaded capture rendering British claims meaningless. A sort of truce which lasted until 1908 followed. But, again, in 1912, 1913 and 1914, trouble between the two sides resumed albeit at a much lower military-level engagement. On the outbreak of World War I, the British moved considerable numbers of their forces

to other theatres. Taking advantage of the situation, the Sayyed consolidated his power base. He started building stone forts atop strategic vantage points which strategically commanded large areas atop hills and mountains in the Sanaag and Sool areas, which, due to the intensity of his war with European, Ethiopian and Somali forces, he was not able to do until then.

During this period, the Sayyed brought more than half of the Protectorate territory under his direct command or influence. The Sayyed, it has been reported, received aid from the Ottomans, Germans and, for a time, from the Emperor Iyasu V of Ethiopia.

By 1919 the Mullah’s hold on Somaliland had become so strong that the British were faced either with abandoning their protectorate or with using a military force estimated at two infantry divisions to deal with the bandit leader. In the bleak postwar economic climate, this was an unaffordable option for the British War Office.

On June 2, 1919, PM Churchill accepted a proposal put to him by RAF Chief of the Air Staff, Sir Hugh Trenchard, for a RAF airstrike against the Sayyed, his forts and followers. A self-contained air component comprising of 10 two-seat de Havilland D.H.9 reconnaissance-bombers, with 36 officers and 183 airmen, was approved.

The RAF built a makeshift base at which was completed on 21 January 1920. Three days later, six RAF D.H.9s took off from the DurElan airfield to initial the first airstrikes on this part of Africa on Sayyed Muhammed’s forts at Medeshi and Jideli, east of Erigavo. The bombing and aerial strafing continued hitting key forts and regrouping grounds until the Sayyed fled to Taleh.

stone forts atop of dervishes headquarter

In early February, after aerial reconnaissance indicated that his forces had reached Taleh, three D.H.9s bombed the fort, one scoring a direct hit on the Mullah’s compound. The Mullah fled the area defeated, and his forces in disarray, crossing over to Ethiopia. 30 In November 1920, the Dervish movement he started as an independence struggle 21 years ago ended with his death in Imey, Ethiopia.

In the period between 1940 and 1941, the country fell briefly under Italian occupation which helped Somaliland parties to gain an insight into what was developing in South Somalia Perhaps, it was this colonial jolt, awakening which further propagating the need for a greater Somali unity since the relationship between the British and Somalis was more on equal terms than the colonial nature of Italy’s outlook on territories it occupied in east Africa.

Contemporary History: Build-up to Independence 1935 – 1960#

Political parties#

The first political party, the Somali National Society (SNS), was founded in 1935. It later transitioned in part to the Somali National League (1945) – perhaps in alignment with its counterpart in Italian Somalia – the Somali Youth League with whom it shared many principles without necessarily actively cultivating them. Mohamed Haji Ibrahim Egal, who was to become later the first Prime Minister of Somaliland led the (SNL). The National United Front (NUF) led by Michael Mariano Ali, the United Somali Party (USP), led by Ali Garad Jama, and many more followed suit between 1945 and 1958.

In the period between 1940 and 1941, the country fell briefly under Italian occupation which helped Somaliland parties to gain an insight into what was developing in South Somalia Perhaps, it was this colonial jolt, awakening which further propagating the need for a greater Somali unity since the relationship between the British and Somalis was more on equal terms than the colonial nature of Italy’s outlook on territories it occupied in east Africa.

In 1943, Her Majesty the Queen of England and Wales, it is reported, offered Somaliland leaders to bring Somali-speaking areas like Hawd and Reserve Area (5th Region of Ethiopia) and NFD (Northern Frontier Districts) under Somaliland administration. The overzealous elements among the yet-to-beseasoned leaders saw it as a hoax to compartmentalize the idea of a Greater Somalia. Hence, they turned it down – a misjudgment that was to regrettably dog Somaliland politics at every turn of its history.

Spontaneous insurrections demanding for an early departure of all foreign occupations later surfaced one of which was led by Sheikh Bashir Haji Yussuf who was later in 1945 tried and hanged by the Brit-ish in Burao. The decade that led to 1960, however, was, for Somaliland politicians, time enough to fully prepare themselves and their nation for full, diplomatically mature, politically and economically capable statehood. ‘At the time of independence there was a strong anti-colonial sentiment sweeping the African continent. Somaliland was no exception. There was a popular drive to unite all the five Somali inhabited territories including Somaliland, Somalia, French Somaliland (Djibouti), Ogaden (Ethiopia), and the Northern Frontier District (NFD) of Kenya. The five pointed white star on the flag symbolized this aspiration.

The 1954 Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement in which Britain transferred 25,000 sq. miles (64,750 sq. km) of ‘Hawd’ grazing land to Ethiopia evoked

an outcry in Somaliland and intensified the demand for a union to recover lost territory ‘ 32 At the time of

independence, there was a strong anti-colonial sentiment sweeping the African continent. Somaliland was no

exception. Eventually, Somaliland had obtained its independence from Great Britain on June 26th, 1960, by the

Royal Proclamation of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth. The independent state of Somaliland was the 15th state

to gain independence in Africa and was immediately welcomed by 35 UN member states included permanent

members of the Security Council. A few days later, Somaliland voluntarily entered into a merger with Italian

Somalia in July 1st 1960 to form the Somali Republic.

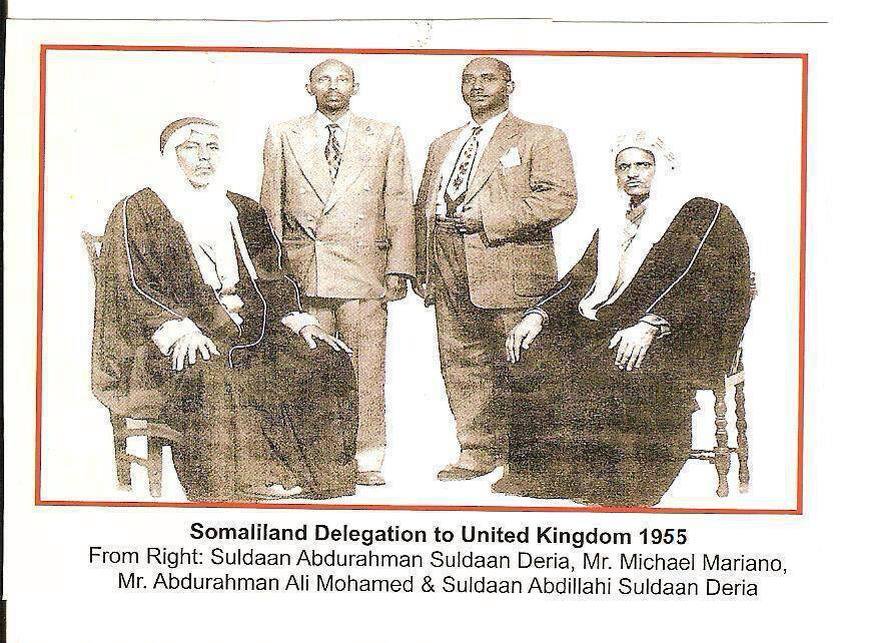

Somaliland Delegation to United Kingdom 1955

The Somaliland Protectorate Constitutional Conference, London, May 1960 in which it was decided that 26 June be the day of Independence, and so signed on 12 May 1960. Somaliland Delegation: Mohamed Haji Ibrahim Egal, Ahmed Haji Dualeh, Ali GaradJama& Haji Ibrahim Nur. From the Colonial Office: Ian Macleod, D. B. Hall, H. C. F. Wilks (Secretary)

The Somaliland Protectorate Constitutional Conference, London, May 1960 in which it was decided that 26 June be the day of Independence, and so signed on 12 May 1960. Somaliland Delegation: Mohamed Haji Ibrahim Egal, Ahmed Haji Dualeh, Ali GaradJama& Haji Ibrahim Nur. From the Colonial Office: Ian Macleod, D. B. Hall, H. C. F. Wilks (Secretary)Referendum on ‘Constitution of Somali Republic’#

In June 1961, an openly rigged, quasi-referendum was conducted in areas in both the former British Protectorate and Italian Somalia to decide whether the two sides would stay together or Apart. The move was meant to quell once and for all the widespread displeasure of northerners of Somaliland to the unequal, south-dominated partnership. Somaliland voted 52% against a constitution of the Somali Republic in 1961, this was a clear sign that the merger between Somaliland and Somalia aborted and failed at the onset.

Coup attempt of Somaliland Military Officials#

In December 1961 – Disaffected Somaliland-born officers attempted a coup de tat to restore Somaliland to its June 26, 1960, independent political status. The coup failed. The attempt was a reflection of the dissatisfaction of the people of Somaliland who correctly predicted the outcome of a merger which began with total domination of the Southern former Italian Somalia against the north Somaliland.

The attempt was, also, an apt interpretation of feelings across the regions of Somaliland as, immediately following the Somaliland politicians’ blunder, all leading positions, among which were the presidency, the prime minister, House Speaker, Chief Justice and the commanders of all of the army, navy, police and custodial corps all went to southern-born politicians and commanders. The usurpation of power and the total abnegation of any vestiges of a ‘union’ were, largely, made a foregone conclusion by the 3:1 ratio balance of the parliament and the government in favor of the south.

Military Coup#

On October 21, 1969, a military junta led by Brigadier-General Mohamed Siyad Barre took over the regions of the country. He took advantage of a vacuum created by the assassination of the then President Abdirashid Ali Sharma’arke in Las Anod on 15 October 1969. He immediately jailed Mohamed Haji Ibrahim Egal, who at long last became a Prime Minister in 1967 following the election of Sharma’arke to the Presidency, under arrest. And so were the whole civilian government were arrested.

The ‘Revolutionary Council’ immediately declared that all political treaties which the civilian governments it took over entered were null and void, thus throwing the last vestiges what was, in essence, a Somalia-dictated ‘merger’ into the wind. To consolidate his authority, the military dictator, SiyadBarre, started a surreptitious plan to build a power base that was ultra-loyal to him and only him. Unbeknown to his comrades within the Council, he began empowering individuals, clans and groups on whom he could rely to consolidate his power base.

One of his first targets was to turn the northern regions – the old Somaliland protectorate – into a military chiefdom governed by hand-picked military governors. It was during the invasion he made on Ethiopia in 1977, on the pretext that he was liberating ‘Western Somalis’, that the military strongman’s plans slowly unfolded becoming visible to the discerning in the form of arbitrary executions of young, brilliant military officers, shooting others on the back, and largely, replacing whole commands to install his hand-picked officers over them. At the end of that short-lived war, Siyad Barre turned his wrath on civilians especially focusing on regions he marked as potential threats to his one-man rule. Somaliland never dimmed in his view as the head of the list.

The Somali National Movement SNM#

One writer puts the emergence of the Somali National Movement (SNM) and its rise to a force to be reckoned with to a reaction to ‘General Barre’s continued atrocities, summary executions, target assassinations, arbitrary arrests, expulsions, freezing commercial activities and, above all, mass starvation of millions of nomads whose livestock and water points had been destroyed by the army forces as part of the eradication campaign’.

Mark Bradbury, states that intellectuals, businessmen and religious leaders founded the SNM as a result of ‘Isaaq disaffection with the regime’ arising ‘from a number of sources: inadequate (and undemocratic) political

representation, unequal distribution of development resources, and government regulation of business, particularly the livestock and qaat trade’ . 34 The ten years between 1981 and 1990 and the events that transpired laid the foundation for the inception and establishment of a restored sovereignty in Somaliland.

A great number of reasons are cited for the rise against the military dictatorship of General Mohamed Siyad Barre. Among these was widespread oppression targeting a major section of the people then living in what was known as the northern regions of ‘Somalia’ – namely the Northwest, Togdheer, Sool and Sanaag regions. A widely reported marginalization, under-development, political, social and economic repression, uneven spread of resources, lopsided power-sharing, capital punishment became the order of the day.

In 1981, the pent up frustration within the Isaaq community was explosively triggered by the government’s arrest of a group of Hargeisa intellectuals, 10 whose only crime was to have organized self-help programs. Accused of distributing anti-government propaganda and other subversive activities, they were handed down sentences ranging from death (later commuted to life imprisonment) to long-term prison sentences. Their detention and torture helped to mobilize national and international condemnation of the regime.

At roughly the same time, consultations within the Isaaq, both within Somalia and in the Diaspora communities of the Gulf, Saudi Arabia, and the United Kingdom, led to the formation in London, of the rebel Somali National Movement (SNM). By 1982, the SNM had established bases in Ethiopia, from where it waged an armed struggle against the regime’s forces in the north, initially in the form of clandestine cross-border incursions.

In January 1983, the SNM campaign gathered momentum with a daring raid on Mandheera Central Prison, which released over 1,000 political detainees and other inmates who had been condemned to death (GOS - Background: 1994).

In return, the government redoubled its campaign of brutal repression. In the urban centers, arbitrary arrests, detentions and executions accelerated. In the rural areas, the regime sought to undermine the SNM’s support among nomads by destroying their livelihoods. Water points were declared off limits, closed, destroyed, poisoned and mined. Commercial trucks were grounded, starving the rural community of food, medicines, and other consumer goods. Villages were razed to the ground and soldiers allowed to confiscate livestock without compensation.35 In the years starting from the inception of the SNM, responding to the socially and politically repressive campaign of the regime against central clans in Somaliland, military commanders were appointed as governors to the then regions of Togdheer, Northwest and Sanaag, and were given free hand to deal with the emerging situation as they saw fit.

Arbitrary arrests, spur-of-the-moment detentions, property impoundment, creation of civilian militias, transfer of large populations from neighboring Ethiopia to take over coastal and agricultural lands and the open segregation of resident clans linked to the SNM became openly and unabashedly the order of the day. It reached a stage where even a private army man transferred to these regions became rich within no time living off the proceeds of bribes, protection money and loots he earned off petrified members of the central clan which formed the bulk of the Movement’s power base.

Ultimately SNM succeeded in liberating Somaliland and defeated the military regime of Siyad Barre in January 1991. The victory of SNM has become the beginning of reinstating the hope and the will of the people to freely determine their political destiny and deepening the fate of peace and political solidarity of the people of Somaliland. The aftermath of the victory of SNM, the SNM controlled that any retaliation should not happen and this has paved the way for the Somaliland tribes and SNM leadership to hold a series political reconciliations and peace building initiatives before the reassertion of the sovereignty.

Extrajudicial Killings#

The government, in attempt to isolate the central clans, wooed other non-Isaaq Somaliland clans into its fold, thus training its whole attention and suppressive tactics against the Isaaqs. It was during the period between 1984 and 1988 that wanton killing in groups or by individuals became the norm of the day – sometimes with flimsy pretexts, sometimes not. The cities of Hargeisa, Burao and Sanaag witnessed mass killings in the name of the law.

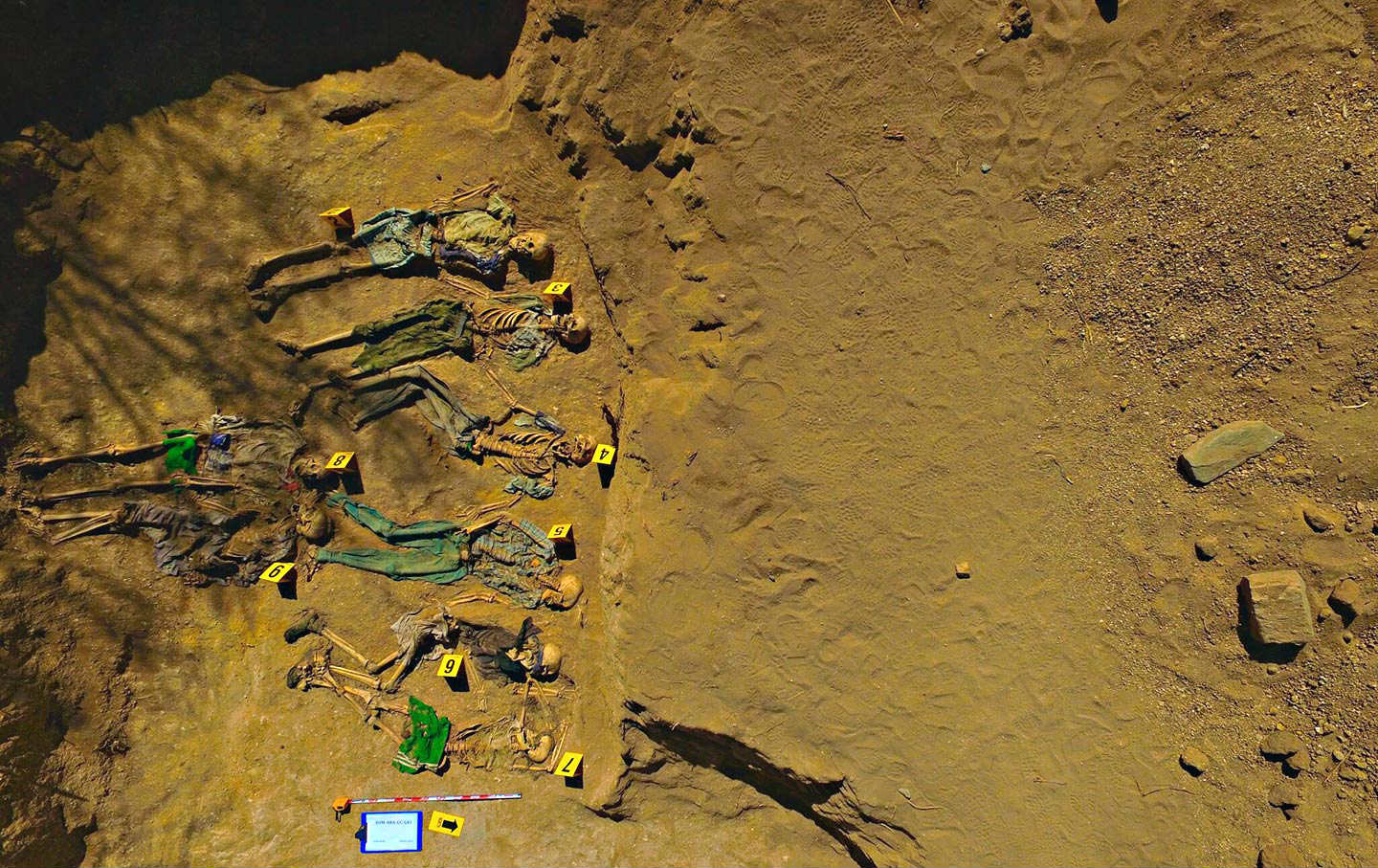

Between 1987 and 1989, the regime of Somali dictator Siyad Barre massacred an estimated 200,000 members of the Isaaq tribe, the largest clan group in the northwest part of Somalia. At the time, some Isaaqs were fighting for independence, and to eliminate the threat, Barre tried to exterminate all of them. Experts now say there are more than 200 mass graves in Somaliland, most of them in the Valley of Death.

In the mid-90s, the Somaliland War Crimes Investigations Commission to document the atrocities, and help experts find mass graves dotted around the country. Shortly afterwards, the Peruvian Team of Forensic Anthropology - Equipo Peruano de Antropologia Forense(EPAF) – started making yearly trips to Somaliland to help the government properly document mass grave. Experts would uncover the mangled skeletons of dozens of victims, some times more than two or three score lumped into one grave, some still tied together.

What was to be discovered defies the imagination. Al Jazeera and Professor Bulhan, between them, tell parts of the story in videos of the same title ‘‘Kill All but the Crows.’’

A 2001 UN report investigating the attacks against the Isaaqs concluded that “the crime of genocide was conceived, planned and perpetrated by the Somalia Government against the Isaaq people of northern Somalia.” But the events have been mostly forgotten; the boys playing soccer did not know the story behind the bones.

Mass Graves

Landmines#

The use of land-mines by government forces against civilians was especially damaging in this particular region due to the majority of Isaaqs (and other northern Somalis) being pastoral nomads, reliant on the grazing of sheep, goats, and camels. A report commissioned by the Vietnam Veterans of America Foundation describes the ramifications of this tactic as follows:40 Such massive mining was part of the destructive and inhumane policies of the Siyad Barre regime impacting on the socio-economy, infrastructure and livelihoods of the people of Somaliland.

Somaliland’s landmines sites